by Jessica Thompson

I stumbled across the concept of subverting expectations while studying the movie Knives Out. This movie felt so revolutionary and perfect, and digging deeper, I found the internet a-buzz with discussions of how this movie used this storytelling tool.

Since I have been studying this lately and was having a hard time grasping it, I decided to write down what I have learned and share it with you.

If you find a good example or think of something I haven’t said, please comment below so we can all learn from each other.

We will talk a lot about movies because they are the most available examples of how to subvert expectations, but this is a principle that you can, and probably should, incorporate into your writing. Before we begin, SPOILER ALERT! We will be ruining The Last Jedi and Knives Out, so go watch those before reading this.

First, definitions.

Subvert – verb gerund or present participle: subverting

undermine the power and authority of (an established system or institution).

(Dictionary.com)

Subvert Expectations

To behave contrary to an established belief or assumption for the purpose of being fresh and interesting. Usually used in the arts when analyzing the reaction of the audience to a performance or piece of writing.

(urbandictionary.com)

Verisimilitude – noun (stay tuned, we’ll get to this)

- the appearance of being true or real.

- having the appearance of truth : PROBABLE

- a theoretical concept that determines the level of truth in an assertion or hypothesis. It is also one of the most essential literary devices of fiction writing. Verisimilitude helps to promote a reader’s willing suspension of disbelief.

(Dictionary.com, Merriam-Webster.com, Masterclass.com)

I don’t know about you, but isolated definitions don’t help me much. I need concrete examples. Popular culture gives us many examples of creators subverting the audience’s expectations–both done well and done disastrously.

Knives Out is a widely accepted example of “subverting expectations” being done well. For one thing, it echoes a traditional mystery in many ways, but then changes from a ‘whodunnit’ to a “how will she get away with this” type story.

The Last Jedi is a widely accepted example of it being done wrong. The example that springs to mind is the fizzled mystery of who Rey’s parents are.

Why is the entire internet comparing these two movies? Because they were done by the same director in quick succession. What did Rian Johnson learn in between making these two films? How to subvert expectations in a satisfying way.

How do we do this as writers? How do you find a fresh way to surprise your readers, but not in a way that feels contrived and unnatural?

According to The Closer Look on YouTube, three things are needed to make the subversion satisfying.

- It needs to serve and improve the story from that point forward

- It must have strong verisimilitude to the story that came before it

- It can’t break promises

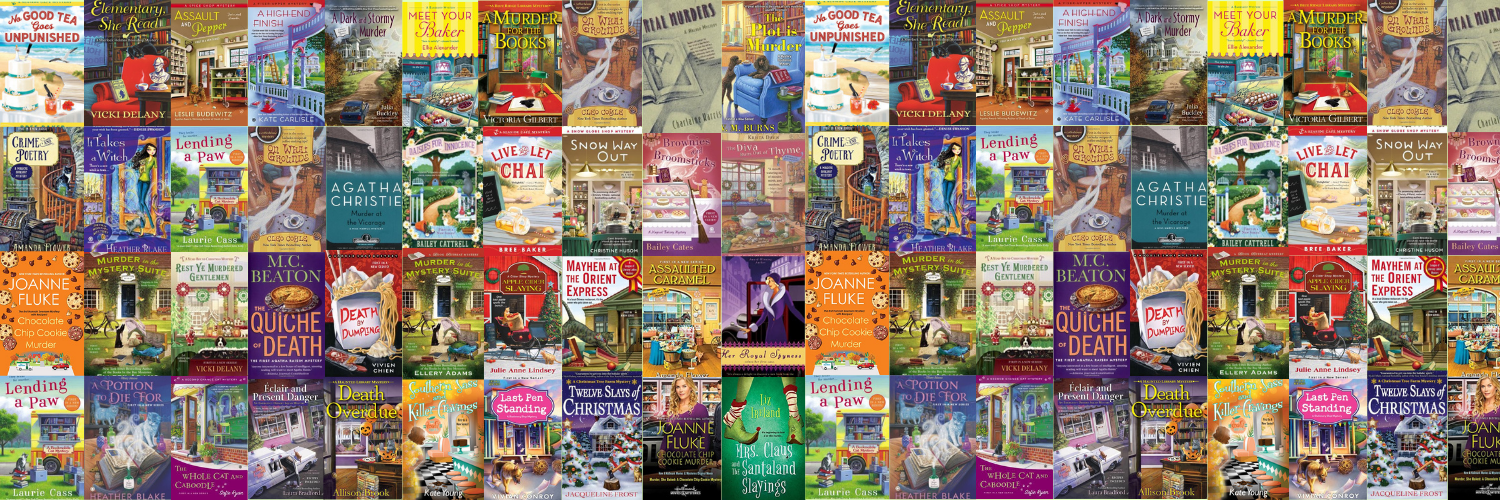

Subverting expectations is a way to break the rules or expectations of storytelling, or the genre, and when done successfully it creates interest or humor. In her day, Agatha Christie did just that by having our main detective be a short, funny-looking Belgian man (Poirot) or a kindly, soft, pink, old spinster (Miss Marple.) Nowadays, subverting expectations is almost the norm. It seems that every movie, especially remakes, have something that recalls expectations and pokes fun.

But it needs to be done in a satisfying way, or the internet will destroy you forever… apparently. So, let’s tackle these one at a time.

- It needs to serve and improve the story from that point forward.

A subversion should only be attempted if it will actually improve the story. If it leaves your reader saying, “what?” or the dreaded, “Yeah, so?” then it has been done wrong. I would say that Luke Skywalker tossing his lightsaber off the cliff was an example of a subversion NOT serving to improve the story. Sure, it showed that he had turned his back on the Force and the ways of the Jedi, but we already knew that. I would argue that it was put in to surprise the viewer, but did not actually improve the story. In a writing class I took from the genius Heather Harper Ellett, she said, “Things should not be put in just to be weird. They have to serve the story.” I would assert that things should also not be put in just for shock value.

Don’t add a subversion that sacrifices your long term story in exchange for an immediate thrill. A good example of this being done wrong is the mini storyline between Finn and Captain Phasma. She was his former commander and essentially should have been his arch rival. As I have learned in my efforts to learn how to write good villains, the good guy should not defeat the bad guy in their first meeting!

Wouldn’t it have been much more powerful if Finn had left Phasma’s unit (as he did,) then faced her and almost been killed, then met her again later after more character growth, as equals and warriors, then defeated her with his old weapon, or maybe hers, and a one-liner that stung? I think so! Even if looking to subvert expectations and mess with that formula, they could have toyed with details and still kept that element of growth and defeating one’s own demons.

Instead, that character arc and growth was abruptly ended by killing her off way too early. I would argue that the director sacrificed the potentially fulfilling longer story of Finn’s growth, in exchange for immediate gratification.

Don’t do that. We’re writers. We play the long game.

I would sum up that it means the subversion has to take the story in a direction, from then on, that is interesting and makes sense, which brings us to our next point.

- It must have strong verisimilitude to the story that came before it.

As we covered in the definitions, verisimilitude refers to how real the subversion seems. Your world can have dragons and magic and zombies, but that is all established in the setup. The subversion that comes later needs to seem “real” within the world that you have set up. It needs to follow the magic rules, align with the timeline that your reader is following in their head, and be in character with the personalities you have already created.

When Luke Skywalker throws his beloved weapon and family heirloom off the cliff, it wasn’t believable because it wasn’t congruent with the story. In Pride and Prejudice, if the haughty and reserved Mr. Darcy had suddenly said, “I’m sorry I’ve been so prideful, I’ll change, will you marry me?,” it would have been totally out of character. If his love interest Elizabeth Bennett, strong and witty, had replied “It’s okay, I forgive you. I’ll marry you” then all readers would have thrown the book down in disgust. That exchange would have not been verisimilar to the characters that Jane Austen had set up. We all know they will eventually get there, but they have a lot more growth to do before that happens, and that’s the essence of the story

Sometimes, a book or movie intentionally and dramatically delivers something contrary to the audience’s expectations. Addressing it outright can help the audience follow along.

When a movie about time travel messes up the movies that came before it, producers call it a “reboot”. We accept that this reboot-time-traveling business is going to logically interfere with the events that occurred in the past or might happen in the future; we’re okay with it because it’s been branded as a reboot. Think of the Terminator and Star Trek franchises. They address and lay to rest the fact that it is not going to line up nicely with your expectations.

When this is done on a small scale, it’s often humorous. This morning, my son’s episode of Hello Ninja had our protagonists in a Wild West situation. Then they said, “The only thing we haven’t done is have a showdown with a bad guy in a black hat.” (Or something to that effect.) Then a rabbit steps out to have a showdown with them. The kids look at his absence of hat, so the rabbit steps out of frame, then comes back with a black cowboy hat. They followed the rules so rigidly that it was funny because they addressed it. In the first X-men movie (the first one made, not talking about the chronology inside the franchise), Cyclops says to Wolverine, “You’d prefer yellow spandex?” It’s a throwback to the cartoon! They gave Wolverine a way better outfit, but then called attention to the tiny subversion of expectations in a funny way! I love it! It didn’t line up with the previously established wardrobe choices of the franchise, but it worked especially well because they poked fun at it.

- It can’t break the promises

In Brandon Sanderson’s video lectures on YouTube, he talks about an author’s “promises” in the setup of the story, and then delivering on those promises. He shares that one of his manuscripts failed at this in the first draft. He says that all of his characters are prepared and determined to go to one place, let’s call it “A,” but he, as the writer knew that the main action was really going to go down in another place, we’ll call it “B.” When the characters got diverted during their travels, essentially as a subversion, and ended up at “B,” the readers thought it was a side story or side quest. They were all waiting for the characters to get back on track and go to “A.” He explains that it was because the promises that he had set up were not kept. The reader did not feel satisfied by this change because it did not keep the promises.

Many critics say the same about the reveal in The Last Jedi about who Rey’s parents are/were. The script that came before had promised a mystery. It had set up that Rey’s parents were somehow important or that it was going to be a significant plot point. Instead, our expectations were subverted in a way that was not satisfying when it is casually revealed that her parents were nobodies and not important to the story. (That changes again later, but that’s another discussion.) That promise was never delivered, so it felt wrong and unsatisfying.

Knives Out, however, circled back and delivered on its promises even though it looked like it might not. When the genre changed from a “whodunnit” to a “how will she get away with this” I was not convinced that we had abandoned the original mystery. I couldn’t anticipate where the story could go after we saw the suicide, but I waited with baited breath to see how it would turn out. The story then came back together and satisfyingly delivered on BOTH storylines and fulfilled all its promises. The ending resolved all my questions and wrapped up everything perfectly.

If you are trying a subversion, make sure you follow all of these guidelines to make it satisfying. Do it right, even if you’re trying to do something new and different. Serve the story that comes before, make it congruent with the story that comes after, and keep your promises to the reader. If you follow these three guidelines, there will still be room for creativity. Done correctly, a subversion improves your story and helps you build a solid relationship with your readers.

Good luck!

AUTHOR BIO

When Jessica discovered mystery books with recipes, she knew she had found her niche. Find her debut novel in paperback and ereader on Amazon now. To order, go to – mybook.to/caterersguide

As an avid home chef and food science geek, Jessica has won cooking competitions and been featured in the online Taste of Home recipe collection. She also tends to be the go-to source about recipes, taste-testing, and food advice among her peers.

Jessica is active in her local writing community and is a member of the Writers’ League of Texas. She received a bachelor’s degree in Horticulture from Brigham Young University but has always enjoyed writing about and reading mysteries.

Jessica is originally from California, but now has adopted the Austin, Texas lifestyle and loves to smoke barbeque, shoot, ride, and wrangle. She enjoys living in the suburbs with her husband and young children, but also enjoys helping her parents with their nearby longhorn cattle ranch.

For additional information about Jessica, please visit her website.