By Jessica Thompson

I have been studying subtext to improve my own writing because I can tell it’s something that my writing has been lacking. This will by no means include every kind or every nuance of subtext, but I’ll share what I’ve learned with you to hopefully benefit us both. If you think of something I missed, please share!

I think we all engage in subtext in our interactions with other people to varying degrees, but we’ve done it all our lives so we don’t really think about it. We probably, myself included, do it more often than we realize because it is simply the meaning behind our actual words. Subtext is what’s going on under the surface of every dialogue all the time. It’s “reading between the lines” or “beating around the bush.” Subtext is the conversation hidden under the conversation. The YouTube channel “The Closer Look” (a particular favorite of mine) cites subtext as the difference between what your characters say and what they mean or think, or I would add, how or why they’re saying it.

Subtext is knowing that someone is not fine when they mope and say, “I’m fine.” It’s how you’re not offended when your friend laughs and says, “I hate you.” It’s the power struggle between Hannibal and Clarice in “Silence of the Lambs” or between Loki and Mobius in the first episode of the show “Loki.”

Subtext is showing meaning instead of saying it. It’s the common “show, don’t tell” principle in writing, but applied to dialogue.

Janet Burroway said it well when she said to “reveal some of their feelings and hide others…”

Ernest Hemmingway called it the Iceberg theory, saying in essence that we as the author need to leave out just enough so the reader knows what’s going on, but its meaning looms large under the surface.

Dialogue should already be purposeful, but subtext gives it a human quality. When people say to write realistic dialogue, I think this is what they mean. They don’t mean to add “ums” and meaningless tangents, they mean to make characters have qualities behind their words. Especially if your characters are facing hard subjects or trying to spare each other’s feelings, subtext is what gives it that “real conversation but better” quality. It’s one of the ways your dialogue can serve more than one purpose at a time. It also creates conflict, builds anticipation, holds attention, and should serve the bigger picture of your story.

Now, before we go on, we should address that subtext is applied differently for different audiences. A children’s book is not going to have the nuances and subtext of a Hemmingway novel. A Disney princess sings about her feelings while a Tarantino character just has a long, drawn out pause in just the right place. Consider the age group and genre that you’re writing for as you apply these ideas in your own work\

So how? How do you show that these characters have their own desires and conflicting emotions?

There are lots of ways, probably more than I could find, but the ways to show subtext that I thought of were body language, tone or timing, when their words disagree with what we already know, analogies and metaphors, when a reaction is too big, sugar coating, implied accusations, and passive aggression or sarcasm.

Body language may be the biggest way to show subtext. It can show our true meaning, especially when it disagrees with the words we’re using. It’s a wife saying “Nothing!” when her lips are drawn tight and she’s folding her arms. It’s James Bond and Miss Moneypenny as she says no but her smirk says yes. It’s not what your characters say, but how they say it. I think a great example of this is in the animated movie, “The Bad Guys.” When our big, bad wolf’s tail starts wagging, we know that he’s feeling the pull to be good, despite how much he calls himself a bad guy.

Tone or timing is another example of how your characters say something showing their true meaning while betraying their actual words. It’s your character yelling, “I’m fine!” right after something has happened to upset them. It’s someone laughing after a joke and saying, “Shut up!” It’s the difference between a girl tittering and saying, “Stop it!” Versus a girl looking you in the eye and declaring “Stop it!” The only example I can think of at the moment is from the movie “Glass Onion” since I saw it yesterday. Without giving anything away, Edward Norton’s character is obviously upset at one point since it’s right after something goes wrong. He has his hands on his hips and is pacing the floor and yelling, but the actual words that come out of his mouth are “I’m not mad. It’s fine.” We know he’s upset, despite what he says, because of his timing and tone (and the body language from our last paragraph too.)

When their words disagree with what we already know, our characters may be hiding their true meaning well, but we as the readers know the truth because it has already been set up for us. Alfred Hitchcock’s “bomb theory” works well here. He said that you must let the audience have information. If two characters talk about baseball for five minutes, it’s boring, but if we are shown that there’s a bomb under the table before the conversation begins, then we know there must be meaning or motive behind the dialogue, we feel the tension, and we’re strung along by the suspense. Basically, if you set up the situation before it arises with ticking clocks, characterization, and purpose, then we know there’s more to the dialogue than just what we see and hear. The best example I can think of is moments when Hercule Poirot, the detective in many of Agatha Christie’s mystery novels, does something silly. His character is already established as careful and methodical, so in moments when he stumbles or figuratively swings and misses, we know that he is up to something. Even though he gives no outward signs, we know there is more to what he’s saying or doing because of information that we already had before the dialogue started. It also helps that he later reveals his true purpose, just in case we forgot about his pillars of order and method.

Analogies and metaphors are some of the most elegant forms of subtext. As examples, you can pretty much count on any time a bag guy starts talking about rats, he’s actually piling on the subtext with a metaphor. Hans Lander in the movie “Inglorious Bastards” goes on a tangent about rats hiding under the floorboards because he’s really talking about the Jewish people hiding from him, a Nazi SS officer. When Silva in “Skyfall” talks about the rats on his grandmother’s island, we know he’s really talking about himself and James Bond. These analogies and metaphors often look like a side tangent at the beginning, but soon they hit a meaning, then tie back in with what the conversation is really about. I think the keys to using this method of subtext are that you have to keep the anecdote or tangent short, then you absolutely have to tie it back in. Hans Lander ends by saying something like “Are they hiding under the floorboards?” to bring the analogy home. Silva also ties his analogy back in by saying something like, “This is what she made us … you see, we are the last two rats.”

Oversized reactions to relatively small issues is an example of something you might not have to tie back in, but hopefully because you have already set up enough information beforehand. It’s when husbands and wives argue over tiny things like the toilet paper being hung the wrong way or who’s going to make dinner. It’s a touch point about a much bigger issue. It’s not about the dinner, it’s about roles in the home or valuing each other’s time. We as humans, and your characters, have big reactions over small things when it’s really about something bigger or deeper. A great example is from “The Great Gatsby” when Daisy is crying about how beautiful Gatsby’s shirts are. Hopefully we all knew that she wasn’t actually crying over the shirts, but it showed that she was deeply feeling the much bigger problem. In my book that will be published in May or June of 2023, called “Shoot Shovel and Shut Up,” the main character finally breaks down when her dad scolds her for meddling. She had been holding it together up until then, despite being surrounded by lethal accidents and murder, but she finally breaks because of this one small incident. It’s the straw that broke the camel’s back. I don’t explain that in so many words, but hopefully I had set up the situation and information in such a way that I didn’t need to explain the real, deeper issue.

Sugar-coating your character’s words is another time that we, or our characters, avoid the real issue. Instead of saying no, they say, “I’m really busy this weekend.” Instead of telling them they’re annoying, or that they don’t love them anymore, a couple breaking up says things like, “It’s not you, it’s me,” or, “This isn’t working.” It’s beating around the bush instead of saying a hard truth. I grew up with a lot of Japanese culture, and in Japan, you don’t say no. That would be entirely too rude. Instead you say, “Chotto …” or other words that translate to things like “Ummm …” or “Well …” Basically any response that’s not an immediate “Yes yes! Wonderful!” really means no. To a lesser extent, that can be true for a lot of situations in your writing. Being persistent or directly pushing through someone’s mild hesitations might be good in some situations in real life, thus resolving conflict and being clear, but if your character is hesitating or dancing around a subject, there’s a reason. That implied reason creates subtext and looming questions, which are what you want in your piece.

Implied accusations may be hard to fit into most conversations, but there are times when they are perfect for creating the right subtext. Again it’s dancing around a subject. It’s asking someone you’re afraid of what they’re doing here. It’s a wife asking where her husband was all night over her mug of coffee the next morning. It’s a simple question on the surface, but it’s shouting the subtext of an accusation. When a person wants to avoid confrontation or a direct accusation would make someone clam up or run away or get angry, they resort to the implied accusation. For an example, think of the first line a detective asks a suspect. You probably know what it is even before I say it. “Where were you on the night of the crime?” Positively dripping with accusation, even though it’s a simple enough question. Since that’s so overused, I wouldn’t even call it an implied accusation anymore. So, don’t use that line, but think of something more subtle.

Passive aggressiveness or sarcasm is another form of subtext where you can’t lay it on too thick. Too much and it’s comical, so watch out for that, unless that’s what you’re going for. “No, no, go ahead,” an overly dramatic mother might say when launching a guilt trip. “Have fun with your friends while I lie here on the kitchen floor. It doesn’t matter that I slaved away over the stove all day!” You know that she’s really saying that she needs to be shown some love and she wants you to stay home for dinner, despite her words saying otherwise. It may not be mentally healthy, but the best characters aren’t. As an example, there was an SNL sketch called “Passive Aggressive Pam.” She had lines like, “Congratulations, your report was actually really useful,” and, “I love your funky thrift-store style.” As the music for the sketch said, her compliments were really slams. So while she’s saying she likes your style, she’s also saying you look like you shop at a thrift store.

Characters rely on all these forms of subtext when they have something to lose. Passive aggressive Pam didn’t want to get into a fight. The police officer implying the accusation doesn’t want the suspect to get so scared that they ask for a lawyer and stop talking. Daisy can’t or isn’t ready to talk about how she regrets her marriage and really wants to be with Gatsby. They aren’t ready to lose their comfort, pride, or happiness. They’re taking a risk, just not all the way. I think of it like flirting. You want to let someone know you’re interested, but not too much in case they reject you. Your characters are just the same. They use subtext when they are at risk.

We, as the authors, need to remember to use our own form of subtext in order to not risk our realism or readers’ immersion in the story.

We need to remember that our themes need to be in subtext. The movie “Interstellar” lost some viewers when Anne Hathaway’s character came out and said that the theme of the movie was love. My editor can tell you that the first drafts of my stories tend to be too heavy-handed with the theme I’m going for. You can’t just come out and say the theme or you may take your reader out of the story, you have to hint at and show the theme. Again, this can be different for different audiences. The middle grade audience needs that theme to be clearer. The adult audience can infer a lot. Also your genre will dictate some of the norms that you have to adhere to, like your musical character can belt out their feelings in a song, but your murderer in a mystery has to give tiny clues that have to be misinterpreted until the time is right.

Some good dialogue doesn’t have subtext? What? I know. Many people argue that there is great dialogue out there without subtext, but I’d like to put it a different way. I say that great scenes that appear to not have subtext instead have subtext that is just in line with the dialogue. The famous Star Wars quote, “No, I am your father,” is cited as an example of dialogue with no subtext. Instead, I say there is still subtext, but it is instead saying the same thing as the words. Darth Vader is reaching out as he’s asking Luke to join him, therefore his body language is telling the same story as his words. Luke is climbing farther and farther away as he’s saying he’ll never join the dark side. His body language, or the vibes he’s giving off as subtext, match his lines. Climactic scenes where characters are pouring their hearts out could be said to be devoid of subtext, but I contend that instead the subtext agrees with the dialogue.

When there really is no subtext, not even subtext that is in line with the dialogue, then the dialogue is crap. Lots of people have lots of problems with “Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones,” especially when Anakin is pouring his heart out to Padme, but I believe this is the real problem with this scene. Some say that he’s using words that no one would ever say, but I disagree. Some people say that this scene shouldn’t have existed and we should instead have only been shown that he loves her, but I also disagree with that. I think it is perfectly fine to have your character have strange speech patterns, especially since they are in line with the character that is already established. And it is great to have a love scene where one character is expressing their love and “walking through the door bow-legged” as my friend says, especially when we have been shown that forbidden adoration in previous scenes.

The true reason that scene between Anakin and Padme was terrible was because Anakin did no showing while he was telling. He was saying how much he loved her while he sat still on a couch. He said he couldn’t breathe, but he didn’t cry or sniffle or gasp. I think he scooched towards her once. That’s it. He made no attempt to touch her or look at her longingly or even pace and torture himself like Mr. Darcy in “Pride and Prejudice.” So, yes, have your characters pour their hearts out, but if things have reached such a crescendo that they have to say the words, make them show us while they tell us.

The last point I want to address is that very special circumstance that I love when the characters themselves aren’t aware of their own feelings until they see these subtext clues along with us. Emma Woodhouse, in “Emma,” doesn’t even know that she loves Mr. Knightley until she discovers it at the same time as us when Harriet’s confession makes her heart pound and rings tears from her eyes. Rachel on the show “Friends” didn’t know that she wanted to have a baby until she found that she was involuntarily saddened by the negative pregnancy test. Something happens and the characters have a knee-jerk visceral response that shows us and themselves their true feelings. The subtext tells the character themselves! Love it! I guess it was a bit of a tangent, but it’s my favorite, so I had to mention it.

Whether you use these devices for subtext or make up your own, I wish you luck in breathing life into your characters through the use of subtext. Again, if you thought of anything that I forgot, please share! Comment below or email me directly. Thanks!

JESSICA THOMPSON

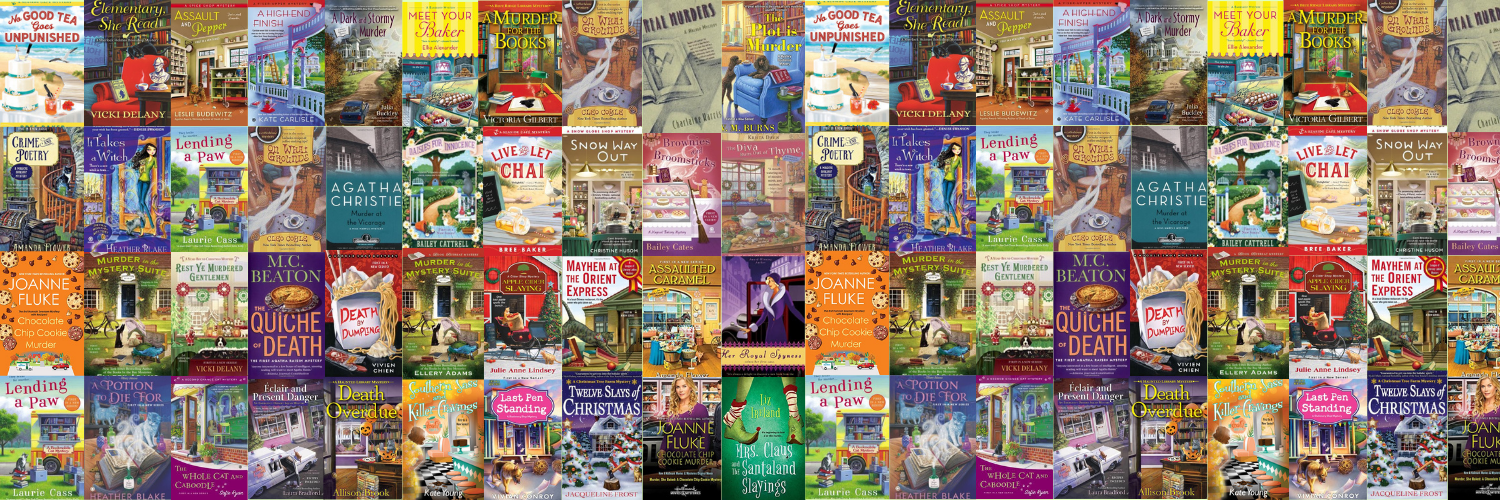

When Jessica discovered mystery novels with recipes, she knew she had found her niche.

Now Jessica Thompson is the author of the Amazon best-selling mystery novels “A Caterer’s Guide to Holidays and Homicide” and “A Caterer’s Guide to Love and Murder” which was a finalist in the Wishing Shelf Awards. She also curated and featured her own short stories in a family friendly anthology of campfire stories, “Beyond the Woods: A Supernatural Anthology.” Active in her local writing community, she volunteers as the Assistant Communications Chair for the Storymakers Guild and as a Program Assistant for the Writer’s League of Texas.

Jessica lives in the suburbs of Austin, Texas with her husband and two children. When not writing, she’s getting her boots dirty at her parents’ nearby longhorn cattle ranch. Whether ranching, cooking, or gardening, she sees it all as plot-inspiring material for her next mystery. Jessica is the author of the Amazon best-selling mystery novels “A Caterer’s Guide to Love and Murder” and “A Caterer’s Guide to Holidays and Homicide.” Her second book was a Whitney Award nominee in the mystery category and her first book was a finalist in the Wishing Shelf Awards. To be published in 2022 is an anthology of short stories that she is curating. Active in the writing community, she volunteers as the Assistant Communications Chair for the Storymakers Guild and as a Program Assistant for the Writer’s League of Texas.

As an avid home chef and food science geek, Jessica has won cooking competitions and been featured in the online Taste of Home recipe collection. She also tends to be the go-to source for recipes, taste-testing, and food advice among her peers.

Jessica lives in the suburbs of Austin, Texas with her husband and two children. When not writing, she’s getting her boots dirty at her parents’ nearby longhorn cattle ranch. Whether ranching, cooking, or gardening, she sees it all as plot-inspiring material for her next mystery.

You Can Learn More About Jessica via Her Website: https://jessicathompsonauthor.com/